07 Bodies We Built

DES

DATE: 2019

Harvard GSD, Master of Architecture Thesis

Advised by Sergio Lopez-Pineiro

Published in Fresh Meat Journal, Volume 13, Isolated Collectives, 2023

Harvard GSD, Master of Architecture Thesis

Advised by Sergio Lopez-Pineiro

Published in Fresh Meat Journal, Volume 13, Isolated Collectives, 2023

Looking into the history of architectural manuals for bodily accommodation, authored throughout history by the likes of Vitruvius, Corbusier, and Neufert, reveals a disciplinary disinterest in indulging an excess of physicality or identity. Architecture and the systems of governance and commerce that produce it appreciate bodies at their most acquiescent, standardized, and ‘good.’ What happens when bodies come to stay awhile? The corpse may be the most acquiescent subject, or perhaps the most radical as it is freed from our lived standards of comfort. But typical spaces for housing the dead are standardized, rigid, and austere. Even in death, bodies are opted-in and conformed to structures and systems of hierarchy and power: heterosexual male bodies laid on the “right” side of their wives, gay, trans, or tattooed bodies excluded from certain necropolises, poor or unknown bodies laid to rest in unmarked mass graves. The expectation, hope, or privilege of having a final resting place reveals that even the dead can’t escape constructed taboos. More exuberant and optimistic than the architectures or landscapes planned to welcome dead bodies are the objects found, purchased, rented, and crafted to commemorate them. This is the material culture of death. In these objects are traces of gender, race, and class - the cleavages that are typically smoothed over in the planning of dead communities.

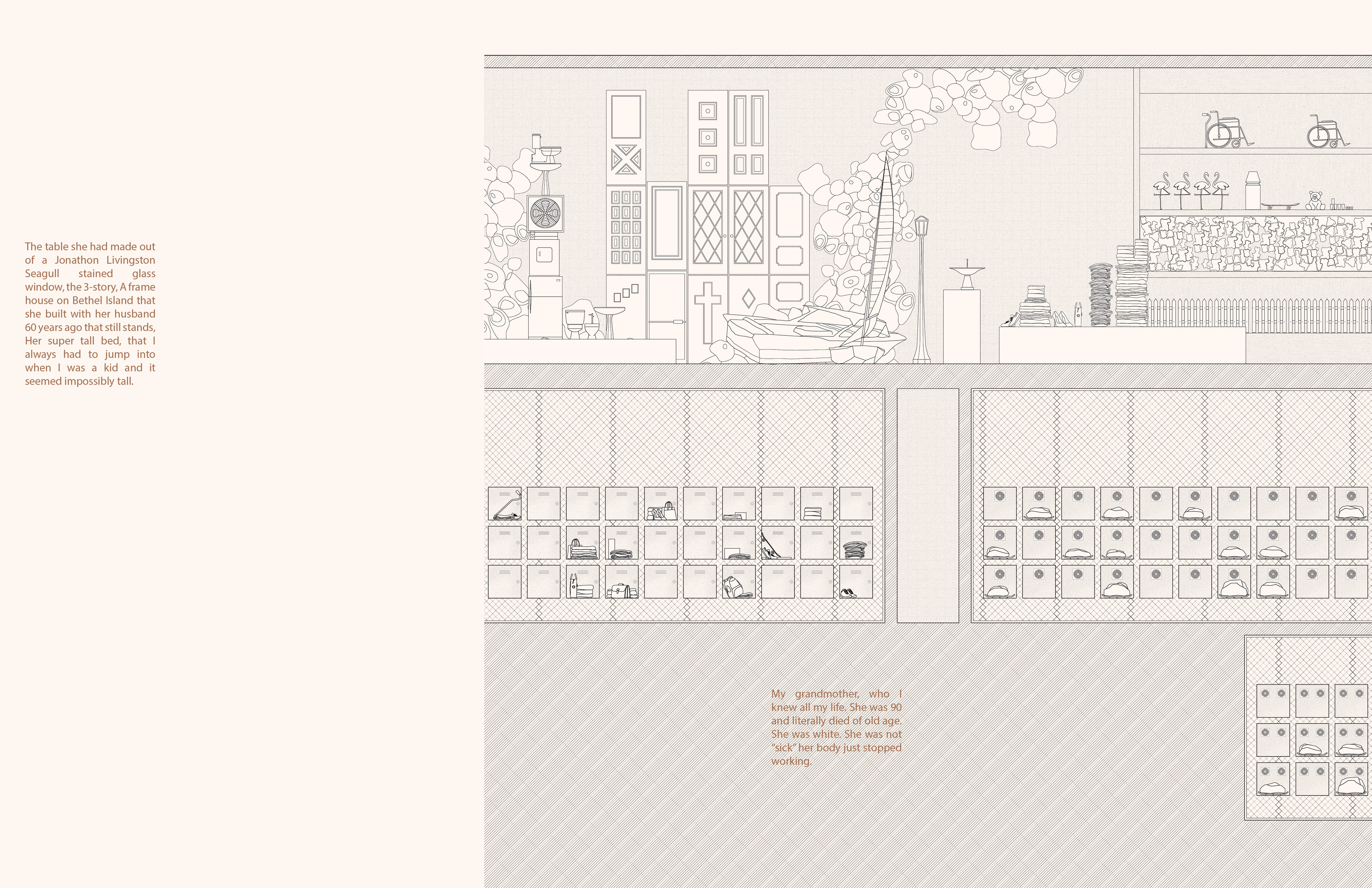

Working towards this flamboyance, 7 characters were studied. They are real, but curated narratives undermine the possibility of a single, final resting place. Instead, bodily legacies are conceived as “construction sites” and illustrate a process of becoming dead. Their bodies pass through spaces with little to no geographic or temporal link and include spaces scaled to the individual body like a coffin, institutions like a prison, and spaces hosted online like a Wikipedia page. Each tells a story about a body, its stuff, its life, and its death. When 7 exuberant deaths combine with stories of death sourced from hundreds anonymous online users via Amazon Mechanical Turk, the question remains of how to accommodate a large constituency of bodies while making room for traces of the individual.

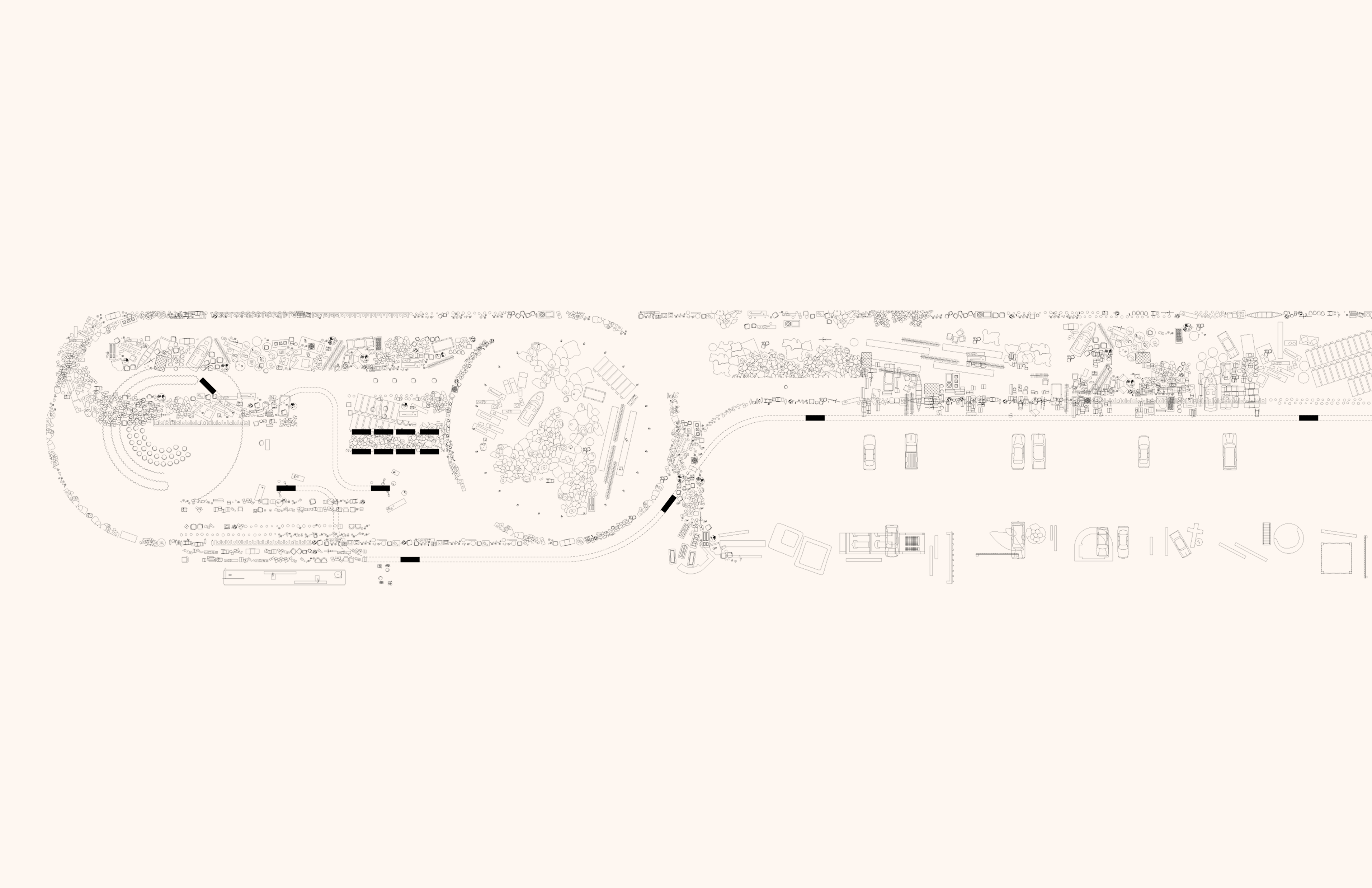

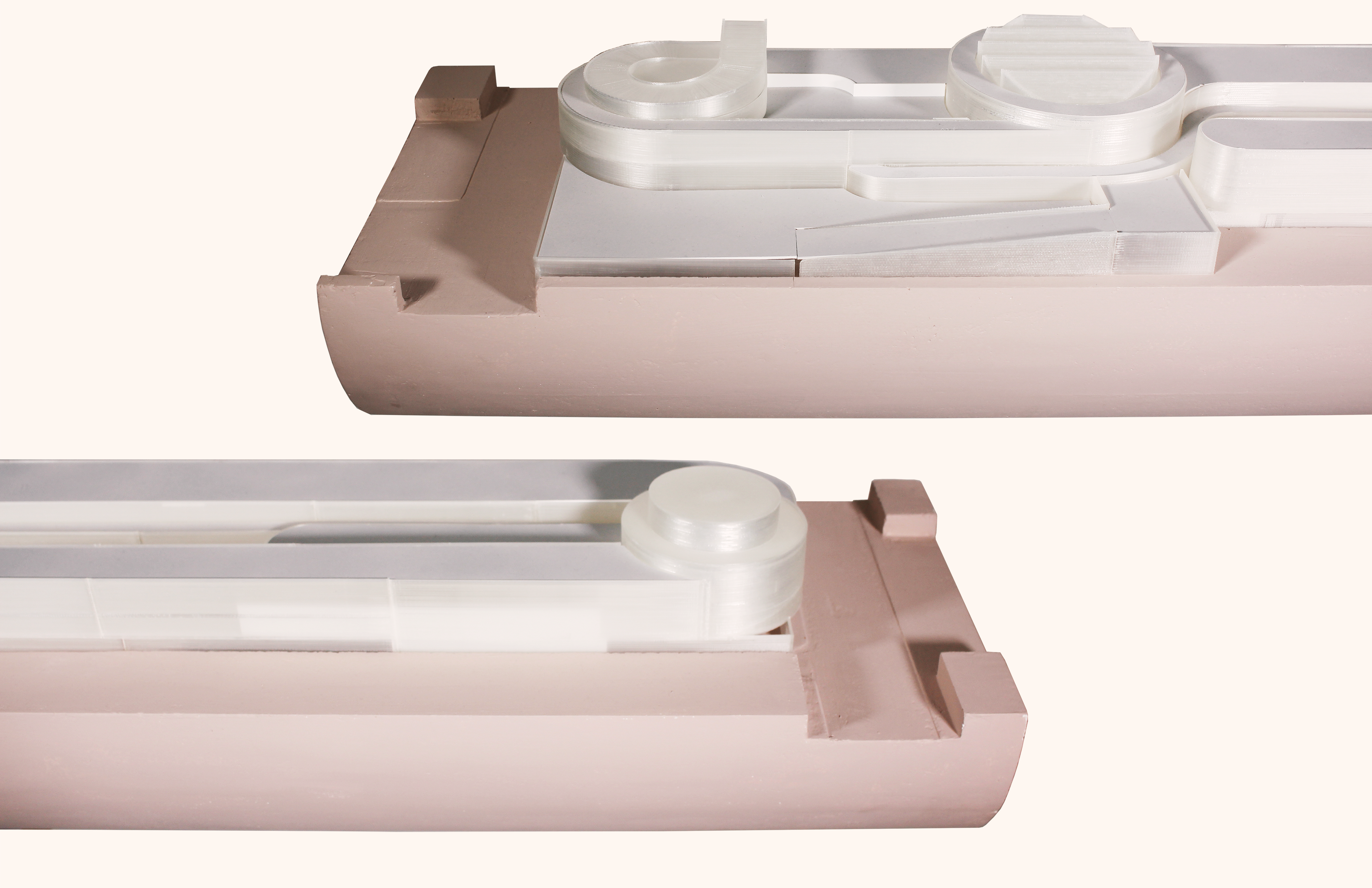

The Illinois Medical District provides a testing ground to situate the exuberance of individual death within institutional collectivity. In Chicago, a city aware but often indifferent to the mortality of (some of) its citizens, the institutional machine for the processing of dead bodies can be found at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office - the city morgue. To reconcile the individual and the masses, the morgue articulates two vectors. The ‘deconstruction of the animate’ handles the breaking down of dead bodies and streamlines a menu of end-of-life treatments. The ‘construction of inanimate’ agglutinates the stuff, the spaces, and the personal. Together and at once, sterilized and standardized spaces accept bodies that leave little to no trace while adjacent spaces accommodate the ever-provisional amassing of objects and effects. An architecture of sequence and accumulation, this thesis makes a case for the idiosyncratic, the hodgepodge, and the mess in the realm of the institutional processing of the dead.

Working towards this flamboyance, 7 characters were studied. They are real, but curated narratives undermine the possibility of a single, final resting place. Instead, bodily legacies are conceived as “construction sites” and illustrate a process of becoming dead. Their bodies pass through spaces with little to no geographic or temporal link and include spaces scaled to the individual body like a coffin, institutions like a prison, and spaces hosted online like a Wikipedia page. Each tells a story about a body, its stuff, its life, and its death. When 7 exuberant deaths combine with stories of death sourced from hundreds anonymous online users via Amazon Mechanical Turk, the question remains of how to accommodate a large constituency of bodies while making room for traces of the individual.

The Illinois Medical District provides a testing ground to situate the exuberance of individual death within institutional collectivity. In Chicago, a city aware but often indifferent to the mortality of (some of) its citizens, the institutional machine for the processing of dead bodies can be found at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office - the city morgue. To reconcile the individual and the masses, the morgue articulates two vectors. The ‘deconstruction of the animate’ handles the breaking down of dead bodies and streamlines a menu of end-of-life treatments. The ‘construction of inanimate’ agglutinates the stuff, the spaces, and the personal. Together and at once, sterilized and standardized spaces accept bodies that leave little to no trace while adjacent spaces accommodate the ever-provisional amassing of objects and effects. An architecture of sequence and accumulation, this thesis makes a case for the idiosyncratic, the hodgepodge, and the mess in the realm of the institutional processing of the dead.