01 Supreme Privacy

EXH - RES

DATE: 2022

Originally exhibited at the Jim Shields Gallery of Architecture and Urbanism. Milwaukee, WI, 2022.

--

Exhibited as part of the Spatializing Reproductive Justice traveling exhibition. Milwaukee, WI, 2024-25 (Curated by Lori Brown, FAIA, Lindsay Harkema, Bryony Roberts, and FLUFFFF Studio; Exhibit designed by FLUFFFF Studio)

Exhibited at the Ewing Gallery of Art and Architecture. Knoxville, TN, 2022-23. (Curated by Liz Teston)

--

Presented at the Public Interiority Symposium at the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Knoxville,TN, 2023.

Presented at the ACSA 111th Annual Conference. St Louis, MO, 2023.

Awarded 2023 ACSA Annual Meeting Best Project Award.

--

Research and installation assistance from Alana Dunne, Evan Johnson, Sarah Lunow, Nathan Magee, and Jacob Rohan

Exhibition photographs by Abigail Platz

Originally exhibited at the Jim Shields Gallery of Architecture and Urbanism. Milwaukee, WI, 2022.

--

Exhibited as part of the Spatializing Reproductive Justice traveling exhibition. Milwaukee, WI, 2024-25 (Curated by Lori Brown, FAIA, Lindsay Harkema, Bryony Roberts, and FLUFFFF Studio; Exhibit designed by FLUFFFF Studio)

Exhibited at the Ewing Gallery of Art and Architecture. Knoxville, TN, 2022-23. (Curated by Liz Teston)

--

Presented at the Public Interiority Symposium at the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Knoxville,TN, 2023.

Presented at the ACSA 111th Annual Conference. St Louis, MO, 2023.

Awarded 2023 ACSA Annual Meeting Best Project Award.

--

Research and installation assistance from Alana Dunne, Evan Johnson, Sarah Lunow, Nathan Magee, and Jacob Rohan

Exhibition photographs by Abigail Platz

Following World War II, as America grappled with the cultural revolution of the 1950s and 60s, and defining its identity domestically and on the world stage, a core tenet of American life bubbled to the surface of political, social, and aesthetic discourse: privacy. Once the revelry of the Allies’ win in the World War cooled into the precarity of the Cold War, American democracy and the culture it afforded its citizens were positioned and advertised, first and foremost, in opposition to the totalitarian government and culture of the Soviet Union.

The notion of privacy - a shapeshifting term so commonplace it evades precise definition - would begin to take on different meanings and manifestations as its aura grew during this era and coincided with the socio-cultural landscape of the late 60s.The trajectory of American life would be forever shaped by this discourse, and Supreme Privacy looks at two layers of American infrastructure - law and the built environment - to explore delineations between privacy and publicness and related delineations between interiority and exteriority.

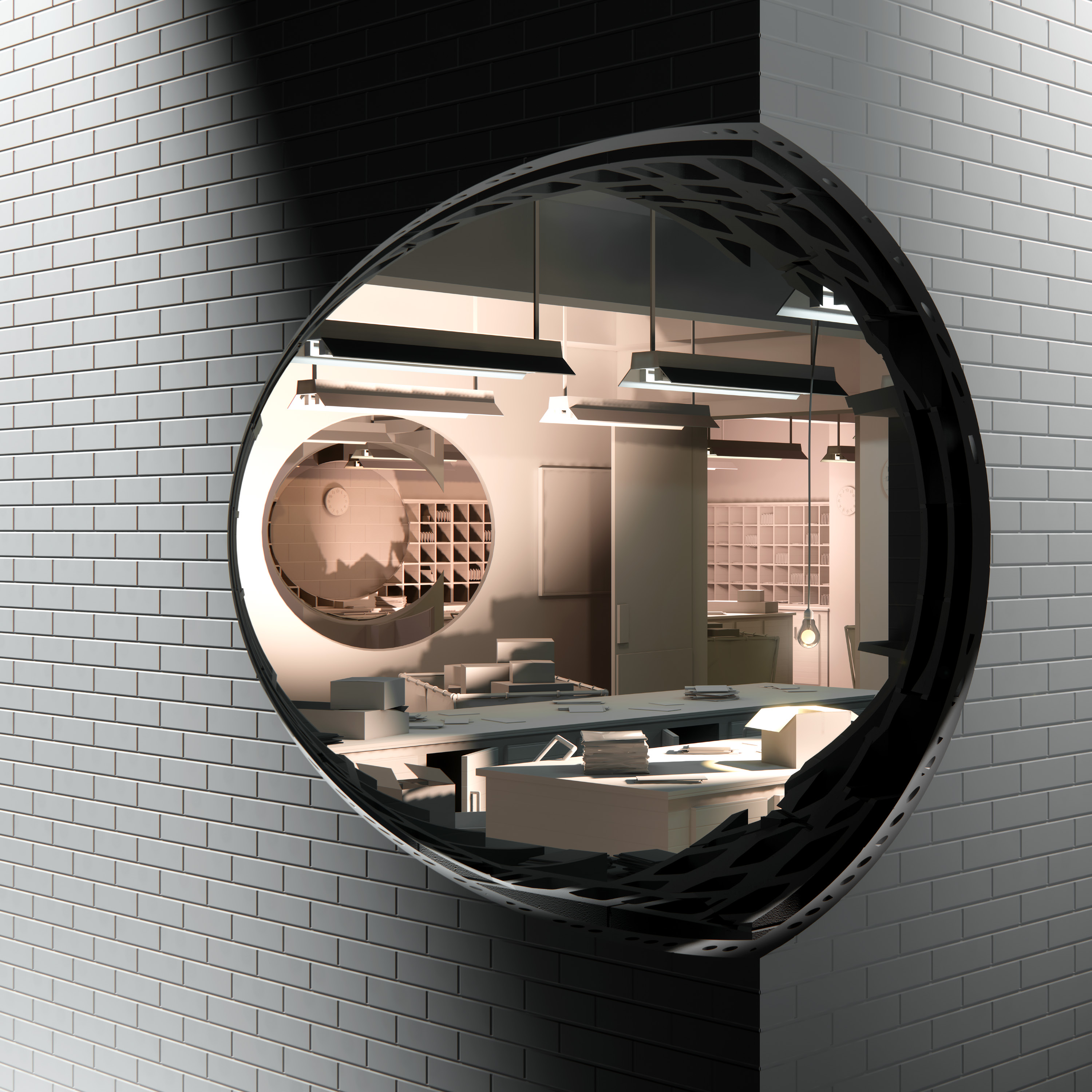

Supreme Privacy explores seven legal-turned-architectural case studies through contemporary written and photographic evidence. The content of original SCOTUS rulings, historical press coverage, and open-access information available on Google Earth facilitate the production of digital mock-ups of the cases’ real architectural settings. For most cases, the exact building or structure where contested events took place is known; in others, a typological placeholder is created. Presented in the digital renderings of these constructed spaces is an architectural “boring sample.” A five-foot-wide cylindrical slice is excavated from each architectural set. The public is invited into private space where the layering of enclosure, furnishings, signage, and other architectural detailing reveals itself in sequence. The unifying cut joins these seven spaces not by typological or aesthetic architectural qualities but by the precedent of spatial privacy they establish as a set. These spaces are not remarkable, but they are relatable and familiar. They reveal the utterly ordinary architectural arrangements that have become historically significant via legalproceedings in the nation’s highest Court. The cases, proceeding chronologically, are as follows:

I. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) is sited at 409 Orange St, New Haven, CT 06511 [see images 1 & 2]. This wood-framed traditional New England two-story residence-turned-fertility clinic is where Estelle Griswold and Charles Buxton ran a reproductive health clinic, the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC). From here, they engaged in advocacy surrounding fertility counseling and awareness. Griswold was the PPLC Executive Director, while Buxton was the PPLC Medical Director and the Department Chair of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Yale University. In addition to organizing border runs to New York and Rhode Island to help married couples obtain contraceptives that were illegal in Connecticut under the Comstock Law, Buxton and Griswold began distributing contraceptives directly from their clinic and were arrested nine days later in 1961.

![]()

II. Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972) is sited at Hayden Hall, 685 Commo

nwealth Ave, Boston, MA 02215 [see image 3]. Described as an “architectural monument to higher education,” in the style of modern Gothic, this masonry structure on the campus of Boston University (BU) is one of BU’s oldest auditorium spaces and where activist William Baird was invited to speak to students about reproductive health and justice. Following his 1967 speech, he gave a 19-year-old unwed student a condom and contraceptive foam and was immediately handcuffed for violating Massachusetts’ Crimes Against Chastity, Morality, Decency, and Good Order laws.

![]()

III. Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) is sited at a typological placeholder: an adoption agency in Dallas, Texas [see image 4]. This generic office space is where Henry McCluskey would’ve practiced as the attorney who helped Norma McCorvey (the previously anonymous plaintiff Jane Roe) organize the adoption of her second and third children from unplanned pregnancies. Though the face of abortion rights, McCorvey never had an abortion herself but sought one out during her third unplanned pregnancy in 1969.

![]()

IV. Carey v. Population Services International, 431 U.S. 678 (1977) is sited at a typological placeholder: a post office in North Carolina [see image 5]. This generic shipping, sorting, and receiving facility is where mail-order contraceptives would have passed through in the 1970s once sent from the North Carolina-based corporation Population Planning Association to recipients in New York state, violating New York’s Education Law.

![]()

V. Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) is sited at the Colorado Club Apartments, 794 Normandy St, Houston, TX 77015 [see image 6]. This triplex-style apartment complex in East Houston is where John Lawrence lived and spent time with his friend Robert Eubanks and Eubanks’ boyfriend Tyron Garner. Following a drunken disagreement in 1998, Eubanks called the police with false accusations against the other two men, resulting in four deputies showing up, entering Lawrence’s residence, and allegedly discovering Lawrence and Garner engaging in a sexual act violating Texas’s “Homosexual Conduct” law. Lawrence and Garner were arrested.

![]()

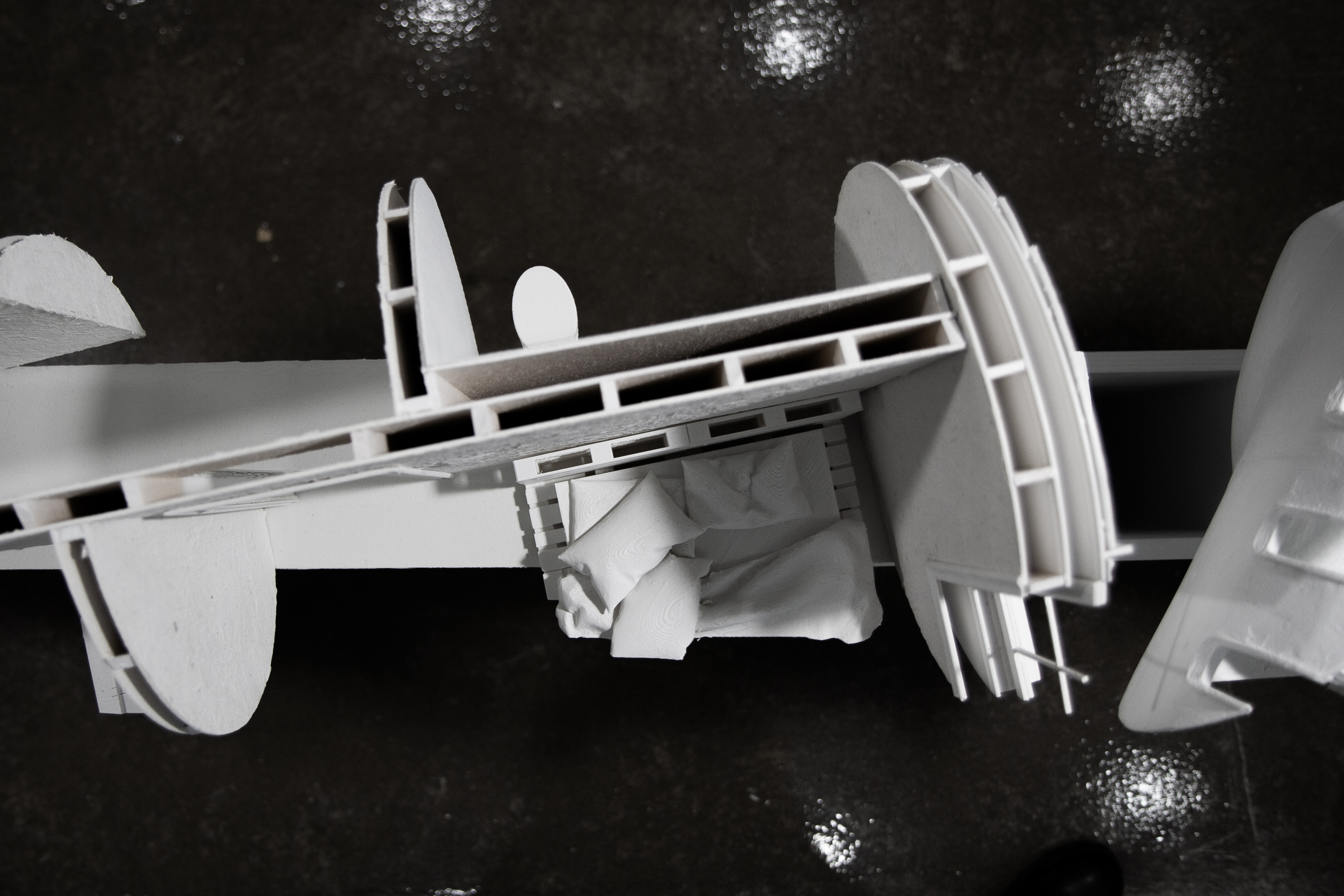

VI. Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015) is sited in a Learjet 45 airplane [see images 7 & 8]. This small, business and medical jet model is a likely candidate for the type of plane flown by Ohio residents John Arthur and Jim Obergefell to be legally married on the tarmac of Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport airport in Maryland. The State of Ohio did not allow same-sex marriage at the time, so as Arthur was terminally ill with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) disease, the two men flew to be married in Maryland in 2013 to then petition for recognition of Obergefell as Arthur’s surviving spouse on his death certificate.

![]()

VII. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U.S. ___ (2022) is sited at the Jackson Women’s Health Organization (JWHO), 2903 N State St, Jackson, MS 39216 [see images 9 & 10]. This pink stucco building, known as the Pink House, is surrounded by a tall wrought-iron fence covered in a black-out fabric screen. JWHO was the last women’s health clinic offering legal abortion procedures in the state of Mississippi.

![]()

The notion of privacy - a shapeshifting term so commonplace it evades precise definition - would begin to take on different meanings and manifestations as its aura grew during this era and coincided with the socio-cultural landscape of the late 60s.The trajectory of American life would be forever shaped by this discourse, and Supreme Privacy looks at two layers of American infrastructure - law and the built environment - to explore delineations between privacy and publicness and related delineations between interiority and exteriority.

Supreme Privacy explores seven legal-turned-architectural case studies through contemporary written and photographic evidence. The content of original SCOTUS rulings, historical press coverage, and open-access information available on Google Earth facilitate the production of digital mock-ups of the cases’ real architectural settings. For most cases, the exact building or structure where contested events took place is known; in others, a typological placeholder is created. Presented in the digital renderings of these constructed spaces is an architectural “boring sample.” A five-foot-wide cylindrical slice is excavated from each architectural set. The public is invited into private space where the layering of enclosure, furnishings, signage, and other architectural detailing reveals itself in sequence. The unifying cut joins these seven spaces not by typological or aesthetic architectural qualities but by the precedent of spatial privacy they establish as a set. These spaces are not remarkable, but they are relatable and familiar. They reveal the utterly ordinary architectural arrangements that have become historically significant via legalproceedings in the nation’s highest Court. The cases, proceeding chronologically, are as follows:

I. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) is sited at 409 Orange St, New Haven, CT 06511 [see images 1 & 2]. This wood-framed traditional New England two-story residence-turned-fertility clinic is where Estelle Griswold and Charles Buxton ran a reproductive health clinic, the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC). From here, they engaged in advocacy surrounding fertility counseling and awareness. Griswold was the PPLC Executive Director, while Buxton was the PPLC Medical Director and the Department Chair of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Yale University. In addition to organizing border runs to New York and Rhode Island to help married couples obtain contraceptives that were illegal in Connecticut under the Comstock Law, Buxton and Griswold began distributing contraceptives directly from their clinic and were arrested nine days later in 1961.

II. Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972) is sited at Hayden Hall, 685 Commo

nwealth Ave, Boston, MA 02215 [see image 3]. Described as an “architectural monument to higher education,” in the style of modern Gothic, this masonry structure on the campus of Boston University (BU) is one of BU’s oldest auditorium spaces and where activist William Baird was invited to speak to students about reproductive health and justice. Following his 1967 speech, he gave a 19-year-old unwed student a condom and contraceptive foam and was immediately handcuffed for violating Massachusetts’ Crimes Against Chastity, Morality, Decency, and Good Order laws.

III. Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) is sited at a typological placeholder: an adoption agency in Dallas, Texas [see image 4]. This generic office space is where Henry McCluskey would’ve practiced as the attorney who helped Norma McCorvey (the previously anonymous plaintiff Jane Roe) organize the adoption of her second and third children from unplanned pregnancies. Though the face of abortion rights, McCorvey never had an abortion herself but sought one out during her third unplanned pregnancy in 1969.

IV. Carey v. Population Services International, 431 U.S. 678 (1977) is sited at a typological placeholder: a post office in North Carolina [see image 5]. This generic shipping, sorting, and receiving facility is where mail-order contraceptives would have passed through in the 1970s once sent from the North Carolina-based corporation Population Planning Association to recipients in New York state, violating New York’s Education Law.

V. Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) is sited at the Colorado Club Apartments, 794 Normandy St, Houston, TX 77015 [see image 6]. This triplex-style apartment complex in East Houston is where John Lawrence lived and spent time with his friend Robert Eubanks and Eubanks’ boyfriend Tyron Garner. Following a drunken disagreement in 1998, Eubanks called the police with false accusations against the other two men, resulting in four deputies showing up, entering Lawrence’s residence, and allegedly discovering Lawrence and Garner engaging in a sexual act violating Texas’s “Homosexual Conduct” law. Lawrence and Garner were arrested.

VI. Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015) is sited in a Learjet 45 airplane [see images 7 & 8]. This small, business and medical jet model is a likely candidate for the type of plane flown by Ohio residents John Arthur and Jim Obergefell to be legally married on the tarmac of Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport airport in Maryland. The State of Ohio did not allow same-sex marriage at the time, so as Arthur was terminally ill with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) disease, the two men flew to be married in Maryland in 2013 to then petition for recognition of Obergefell as Arthur’s surviving spouse on his death certificate.

VII. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U.S. ___ (2022) is sited at the Jackson Women’s Health Organization (JWHO), 2903 N State St, Jackson, MS 39216 [see images 9 & 10]. This pink stucco building, known as the Pink House, is surrounded by a tall wrought-iron fence covered in a black-out fabric screen. JWHO was the last women’s health clinic offering legal abortion procedures in the state of Mississippi.